Epistemic and Aleatoric Uncertainty in Machine Learning

Published:

Epistemic and Aleatoric Uncertainty

Introduction

Uncertainty quantification in machine learning (ML) is critical for safely and effectively deploying models in real-world scenarios, for enhancing training efficiency, and for supporting informed decision-making processes. Consider a medical application where a machine learning model predicts whether a patient has cancer from a scan of the patient. Quantifying the model’s uncertainty is crucial for determining when to rely on the model’s predictions or when to defer to human experts. Moreover, during the training of ML models, understanding which data points a model is uncertain about and whether this uncertainty stems from not having seen a certain type of data before or from the inherent noise or ambiguity in the data, can guide targeted additional training for best improving a model’s performance.

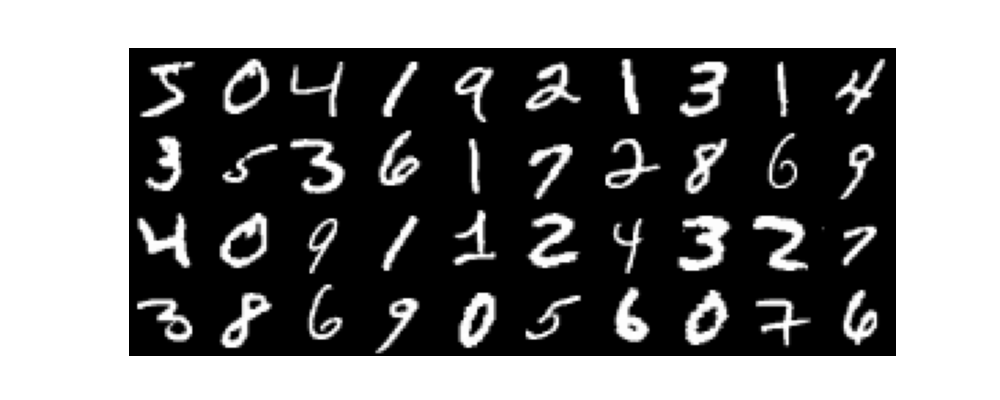

Figure 1: Examples of images from the MNSIT dataset consisting of 28 x 28 greyscale images of handwritten digits2024-02-03-epistemic-and-aleatoric-uncertainty-in-machine-learning.md

In this blog post, we introduce two forms of uncertainty that are particularly important in ML, namely epistemic (reducible) and aleatoric (irreducible) uncertainty. We aim to illustrate these two types of uncertainty using a classification task within ML as a running example, and highlight why quantifying and even untangling each type of uncertainty is important within the context of ML.

We will consider the running example of solving a classification problem under a frequentist setting. By “frequentist setting,” we refer to the approach of training on a specific dataset to obtain a fixed final model at the end of training . This fixed model can then be used to make predictions on new and unseen data.*

Imagine that we have a collection of images, each labeled as belonging to one of $K$ distinct classes. The classification task involves using a model, such as a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [3] or a Vision Transformer ViT, to take an image as an input and predict the specific class that the image belongs to. For a more tangible example, we will focus on a classification model trained on the MNIST dataset [1]. As can be seen in Figure 1, this dataset comprises $28 \times 28$ greyscale images of handwritten digits, ranging from $0$ to $9$. Our model, after being trained on the training portion of this dataset, is capable of taking an arbitrary image of a digit from the MNIST test dataset (images it has not seen before), and predicting the digit’s class i.e. what digit from $0$ to $9$ the model thinks is in the image.

As can be seen in the Figure 2, the model doesn’t just predict the class for an image; it also provides a confidence level or prediction probability for each class, indicating how strongly the model believes the image belongs to a particular class or contains a particular digit. Note that the probabilities over all classes sum to $1$ which is what we would expect if these class beliefs are to accurately reflect probabilities. We take the class with the highest prediction probability as our model’s prediction of which digit is depicted the input image.

![Figure 2: Image classification model with class prediction probabilities for an example input image from the MNIST dataset. The image of cogs was generated by OpenAI’s ChatGPT [2].](/images/figure_2.png)

Figure 2: Image classification model with class prediction probabilities for an example input image from the MNIST dataset. The image of cogs was generated by OpenAI’s ChatGPT [2].

*In future posts we will consider a Bayesian setting where we don’t obtain a single model after training as in the frequentist setting, but we consider a whole distribution of different models. In particular, we use the data observed during training to discern which of these possible models are more likely than others to reflect the underlying function that we’re trying to model. In the Bayesian setting, we will look at the distribution of possible models as a way of quantifying uncertainty. Stay tuned!

What is aleatoric uncertainty?

Aleatoric uncertainty is the first component of uncertainty that we will focus on. In a nutshell, aleatoric uncertainty refers to the uncertainty of our model stemming from the inherent noise or ambiguity within our data that can’t reduced through additional data. Let us consider two examples to illustrate these points.

Firstly, consider Figure 2 again. Here, the image clearly contains the digit $7$. As we can see, the model also predicts this, predicting this image depicts a $7$ with a high likelihood of $85%$$\%$. Our model is confident that the image is a $7$ and based on its prediction probabilities, is displaying low uncertainty in its predictions in that it isn’t assigning any significant likelihood to any other digit.

![Figure 3: Model predictions on ambiguous image. Cogs image generated by OpenAI’s ChatGPT [2].](/images/figure_3.png)

Figure 3: Model predictions on ambiguous image. Cogs image generated by OpenAI’s ChatGPT [2].

Now consider Figure 3. Here, the model is presented with an image that is ambiguous or ‘noisy’. In particular, this digit could realistically contain a $0$ or a $9$. We can see that the model assigns high probabilities to both of these outcomes indicating that it is rather uncertain about which class the image belongs to; the model is indicating that both options are highly plausible. No matter how many clear examples of $0$s and $9$s we or the model see in the data, this is never going to help the model or us as humans determine whether this specific unclear image is definitely a $0$ or a $9$ - there’s always going to be some level of uncertainty in our answer. This illustrates an inherently noisy and ambiguous image for which our uncertainty can’t be reduced by training on more data. We would say that the uncertainty shown by the model is aleatoric in nature. In real-world scenarios, we could consider images taken under varying lighting conditions or data from sensors that contain measurement errors as examples of data that can be noisy and ambiguous.

Focussing on the predictive distribution (that is the different class prediction probabilities) in Figure 3, we see that there is quite a spread of probability between two plausible classes. Indeed the model is assigning high likelihood to both $0$ and $9$. This is sharp contrast to the example presented in Figure 2 of clear image of a $7$. The model assigns most of its probability mass, which you can think of as its “belief budget”, to the digit $7$. In some sense the overall distribution or probabilities over class labels for the image of a $7$ is less spread out or in some sense “less random”, and the distribution is `more deterministic’ or focussed on a particular class.

A probabilistic tool that we can use to measure the spread of probability in a distribution is the entropy of the distribution [5]. Roughly, higher/lower entropy indicates a greater/lower spread in the probabilities within a distribution. A maximum entropy distribution in our scenario would assign each class an equal likelihood of being correct, indicating maximum randomness in the model’s predictions. On the other extreme, a minimum entropy distribution would be where all of the probability is placed on a single outcome, indicating that the model is certain of a particular outcome. In this scenario, there is no randomness - its deterministic. The entropy of a distribution gives a quantitative measure of the spread in a distribution between these two extremes. Because of this, entropy can be used to more concretely frame our discussion above concerning the spread of probability in the predictive distribution of a model and thus help to quantify forms of uncertainty more concretely. We’ll come back to this concept in our next post. *

Finally, let us consider presenting our model with a $28 \times 28$ pixel image of the letter $\texttt{v}$. Given that the model has been trained exclusively on images of digits, it has never encountered letters within its training dataset. As illustrated in Figure 4, the model’s response to this unfamiliar type of image is to predict a range of possible digits, essentially making guesses without a clear basis. At first glance, one might question if this uncertainty stems from aleatoric sources. However, the image of the letter $\texttt{v}$ is neither noisy nor ambiguous to us; it is perfectly clear and identifiable as we have seen similar types of images before, the model hasn’t. This observation indicates that the uncertainty displayed by the model is not aleatoric, as it does not arise from data noise or inherent ambiguity, but from a lack of experience with certain types of examples. This uncertainty could be reduced with more data and experience with this new type of image. This leads us onto a discussion of epistemic uncertainty.

![Figure 4: Model predictions on a OOD image of a $\texttt{v}$. Cogs image generated by OpenAI’s ChatGPT [2].](/images/figure_4.png)

Figure 4: Model predictions on a OOD image of a $\texttt{v}$. Cogs image generated by OpenAI’s ChatGPT [2].

*This discussion of entropy was a little hand-wavy but hopefully gives some intuition of its use in quantifying how spread out the probabilities in a distribution are. Entropy, in the context of information theory, quantifies the amount of uncertainty or surprise associated with a random variable’s possible outcomes. In the next post, we’ll give more details about entropy, including giving its definition and some concrete examples of calculating it for several distributions.

What is epistemic uncertainty?

We now focus on the second type of uncertainty mentioned in the introduction, epistemic uncertainty. Epistemic uncertainty can be thought of as the uncertainty of our model that stems from a lack of knowledge or experience and that can be reduced with additional data. This in contrast to aleatoric uncertainty that is due to noise or ambiguity n the data and cannot be reduced with additional data.

Consider the example of learning a new language, say French. We will observe a words that we have never seen before like $\texttt{la fraise}$. Maybe we can make some guesses on what we think this word could mean that could be extrapolated based on what we already know, like we can see that it is a feminine noun. But, if we have never seen this word before we would be uncertain and somewhat clueless as to what this word actually translates to in English. However, once we have learn this work, $\texttt{la fraise - strawberry}$, we reduce our uncertainty for this and related examples. In particular, we could now recognise the plural form $\texttt{les fraises}$ and understand it in context, for example: $\texttt{Est ce-que vous avez des fraises? - Do you have strawberries?}$

Following on from the previous example, now consider the statement $\texttt{le vol a été facile}$ for translation in a French language quiz. The word $\texttt{vol}$ introduces inherent ambiguity without context, as it could mean either $\texttt{theft}$ or $\texttt{flight}$, leading to two valid translations: $\texttt{the theft was easy}$ or $\texttt{the flight was easy.}$ This ambiguity exemplifies aleatoric uncertainty, where the challenge isn’t due to a lack of knowledge about the word $\texttt{vol}$ and its meanings. Instead, it arises from the intrinsic ambiguity (really polysemy) of the word $\texttt{vol}$ itself, highlighting a situation where uncertainty remains irreducible without additional context even if we were to practice translating many more sentences from French to English. *

Going back to our classification example, we considered showing our model an image of a $\texttt{v}$ when the model has only every been trained on and has seen images of a digits. This image is not inherently noisy in the sense that we can identify that this is indeed an image containing the letter $\texttt{v}$ as opposed to some other letter or a digit. We call such a point out-of-distribution (OOD) for the model as it comes from a collection or distribution of images that our model has not seen during training and is therefore unfamiliar with. By subsequently including images of the letter $\texttt{v}$ in the model’s training dataset, we would effectively bridge the model’s knowledge gap. This augmentation of the dataset allows the model to learn and recognise new patterns—specifically, the shape and form of $\texttt{v}$. As a result, the model’s previous uncertainty when encountering $\texttt{v}$-like images diminishes, it will no longer be less familiar with this type of image. This practical step demonstrates how epistemic uncertainty, rooted in the model’s unfamiliarity with certain data, is directly reducible by expanding its experience with those very data types. In this case the uncertainty that our model is exhibiting is an example epistemic uncertainty. Note that this contrasts with aleatoric uncertainty, where additional data does not alleviate the uncertainty due to the inherent noise or ambiguity in the observations themselves. This is the key distinction between aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty: irreducible vs reducible uncertainty. Reducing epistemic uncertainty can also involve strategies beyond adding additional dataset examples in order to reduce the uncertainty in a model due to lack of knowledge. Other strategies include integrating domain knowledge or techniques like transfer learning can also help to address the model’s knowledge gaps. We refer the reader to the following papers [8,9].

In our discussion of epistemic uncertainty, we have noted how models can display a wide spread in their predictive distributions over classes when encountering unfamiliar images, exemplifying uncertainty that is epistemic in nature. However, relying solely on the predictive distribution for quantifying epistemic uncertainty in a frequentist setting presents challenges, particularly due to models’ tendency towards overconfidence [10, 11]. This overconfidence—where a model often assigns unjustifiably high probabilities to certain classes—undermines the reliability of using predictive distributions as a straightforward measure of uncertainty. This because particularly problematic for out-of-distribution (OOD) data, where the model can present misleadingly high likelihood predictions for a certain class even when the model confronts entirely new types of data where our model should be naturally be less certain. Moreover, in real-world scenarios with significantly more complex data like patient scans in medicine, identifying whether a high entropy or spread out predictive distribution is indicative of aleatoric or epistemic uncertainty can be much more difficult even for human experts when inspecting the original labelled image, meaning the use of of the predictive distribution alone for disentangling and enacting on uncertainty becomes more complicated. One principled approach to mitigate the aforementioned issues when relying on the predictive distribution of a model in the frequentist setting for identifying and disentangling uncertainty is the adoption of a Bayesian framework. Within a Bayesian framework, we express our beliefs about different possible models that could explain the data we observe, rather than committing to one single model at the end of training as in the frequentist setting. By taking beliefs about different plausible models, Bayesian methods often lead to more robust predictions that suffer less from overconfidence. Moreover, we can disentangle the uncertainty more rigorously within this context. We will delve into the Bayesian setting in more detail in our next post!

*Taking about uncertainty in language can be tricky. Take this example, if we were to allow for additional context to clarify ambiguous translation, then this uncertainty would now be more akin to epistemic uncertainty due to being reducible - for example if we were told that this is in the general context of someone arriving at an airport then we would be much more certain that the translation should be $\texttt{the flight was easy.}$ For further reading, the following papers discuss the interplay between language, clarifications and uncertainty [6,7].

Why are these two concepts important?

Understanding and quantifying the two types of uncertainty—epistemic and aleatoric—is crucial for machine learning (ML) practitioners, especially when training models with limited datasets and compute resources. It is important in such setting to being sample-efficient, allowing your model to learn and improve the most from the least amount of data. For instance, consider a model trained on a dataset of MNIST digits only containing the digits $0$ to $8$. This model has never seen an image containing the digit $9$. introducing this digit significantly reduces the model’s epistemic uncertainty about future $9$ examples by filling a gap in its knowledge. Showing many images of $0$s which the model may already have a good grasp in identifying is going to be a lot less impactful on improving the model than introducing images of the digit $9$.

As a more topical example, lets turn to the task of fine-tuning large language models (LLMs), such as autoregressive models trained to predict the next token based on previous ones, often using vast amounts of unlabelled text in an unsupervised setting. These pre-trained models’ expressiveness can be harnessed for downstream tasks like sentiment analysis (predicting whether a price of text expresses positive or negative sentiment for example), where labelled data may be scarce. Methods like LoRA [12] are still relatively resource-intensive even while being one of the more efficient fine-tuning approaches for LLMs given the shear size of language models used today. Therefore, we need to look for and utilise data that for fine-tuning that is going to be most impactful for improving downstream performance on the sentiment analysis task. Take the ambiguous text $\texttt{Interesting experience, wasn’t it?}$ Without additional context, determining whether this implies positive or negative sentiment is challenging. More examples of clear positive or negative sentiment won’t necessarily clarify the sentiment analysis of such ambiguous statements. This ambiguity represents aleatoric uncertainty, intrinsic to the data, and training our model on similar examples won’t improve model performance on the sentiment analysis tasks. Instead, focusing on reducing epistemic uncertainty—uncertainty due to the model’s lack of exposure to specific types of examples—promises the most significant performance gains. Therefore, the ability to quantify and differentiate between epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty is essential in this context, enabling more informed decisions about data selection for training and fine-tuning models, especially under constraints of data and computational resources.

Concluding Remarks

We hope that the discussion on epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty, their distinctions, and the importance of quantifying them has been a useful introduction to the general area. However, we have only scratched on the topic of uncertainty and its quantification in ML. A few points that are worth keeping in mind going forward:

- Calibration: Our conversation touched upon predictive probabilities and how they can be used in quantifying some form of uncertainty. However, for these to be genuinely informative, they must be well-calibrated. Calibration ensures that a model’s predicted probabilities accurately reflect the likelihood of an event occurring. For instance, if a model assigns a $70\%$ probability to a specific classification, ideally, $70\%$ of those predictions should be correct. This aspect of model reliability, where predicted probabilities match observed outcomes, is crucial for making meaningful predictions and reasoning with the associated class probabilities for instance in uncertainty quantification, especially within safety-critical contexts like healthcare. More concrete details on calibration can be found in [13, 14, 15]

- Quantifying Epistemic Uncertainty: We’ve also noted the challenges in identifying out-of-distribution (OOD) points due to models’ tendency towards overconfidence and their struggles with generalisation in a frequentist setting. This raises the question: How can we effectively quantify epistemic uncertainty? Various methodologies exist, from more principled Bayesian approaches to other heuristic approaches [16, 17, 18]. These strategies offer different ways to quantify uncertainty, each with its merits and limitations, which we’ll explore in upcoming posts.

- Interconnection of Uncertainty Types: Although aleatoric and epistemic uncertainties might seem distinct based on our initial discussion, they are intrinsically linked. A Bayesian viewpoint, which we will delve into next time, elegantly bridges these two types of uncertainty, offering a single cohesive framework for understanding and quantifying these two types of uncertainty for ML models [16].

In conclusion, understanding and quantifying uncertainties in ML is a complex but critical for reasoning with and deploying ML models in practice. It enhances model reliability, informs better decision-making, and guides the efficient allocation of resources. As we advance, we’ll uncover more about these concepts and the different approaches in quantify and reasoning about them in different ML contexts.

References

[1] Deng, L. (2012). The MNIST database of handwritten digit images for machine learning research. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, 29(6), 141–142.

[2] OpenAI. (2024). OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT 4 [Software].

[3] LeCun, Y., Kavukcuoglu, K., & Farabet, C. (2010, May). Convolutional networks and applications in vision. In Proceedings of 2010 IEEE international symposium on circuits and systems (pp. 253-256). IEEE.

[4] Dosovitskiy, A., Beyer, L., Kolesnikov, A., Weissenborn, D., Zhai, X., Unterthiner, T., … & Houlsby, N. (2020, October). An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

[5] Bishop, C. (2006). Pattern recognition and machine learning. Springer google schola, 2, 531-537.

[6] Hou, B., Liu, Y., Qian, K., Andreas, J., Chang, S., & Zhang, Y. (2023). Decomposing Uncertainty for Large Language Models through Input Clarification Ensembling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.08718.

[7] Kuhn, L., & Gal, Y. (2022, June). 1. CLAM: Selective Clarification for Ambiguous Questions with Large Language Models. In International Conference on Machine Learning.

[8] Zhuang, F., Qi, Z., Duan, K., Xi, D., Zhu, Y., Zhu, H., … & He, Q. (2020). A comprehensive survey on transfer learning. Proceedings of the IEEE, 109(1), 43-76.

[9] Xie, X., Niu, J., Liu, X., Chen, Z., Tang, S., & Yu, S. (2021). A survey on incorporating domain knowledge into deep learning for medical image analysis. Medical Image Analysis, 69, 101985.

[10] Hendrycks, D., & Gimpel, K. (2016, November). A Baseline for Detecting Misclassified and Out-of-Distribution Examples in Neural Networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

[11] Liang, S., Li, Y., & Srikant, R. (2018, February). Enhancing The Reliability of Out-of-distribution Image Detection in Neural Networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

[12] Zhang, H., Li, G., Li, J., Zhang, Z., Zhu, Y., & Jin, Z. (2022). Fine-Tuning Pre-Trained Language Models Effectively by Optimizing Subnetworks Adaptively. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35, 21442-21454.

[13] Joy, T., Pinto, F., Lim, S. N., Torr, P. H., & Dokania, P. K. (2023, June). Sample-dependent adaptive temperature scaling for improved calibration. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (Vol. 37, No. 12, pp. 14919-14926).

[14] Bella, A., Ferri, C., Hernández-Orallo, J., & Ramírez-Quintana, M. J. (2010). Calibration of machine learning models. In Handbook of Research on Machine Learning Applications and Trends: Algorithms, Methods, and Techniques (pp. 128-146). IGI Global.

[15] Guo, C., Pleiss, G., Sun, Y., & Weinberger, K. Q. (2017, July). On calibration of modern neural networks. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 1321-1330). PMLR.

[16] Mukhoti, J., Kirsch, A., van Amersfoort, J., Torr, P. H., & Gal, Y. (2023). Deep Deterministic Uncertainty: A New Simple Baseline. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 24384-24394).

[17] Osband, I., Wen, Z., Asghari, S. M., Dwaracherla, V., Ibrahimi, M., Lu, X., & Van Roy, B. (2023). Epistemic Neural Networks. In Thirty-seventh Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems.

[18] Liu, J. Z., Padhy, S., Ren, J., Lin, Z., Wen, Y., Jerfel, G., … & Lakshminarayanan, B. (2023). A simple approach to improve single-model deep uncertainty via distance-awareness. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 24(42), 1-63.